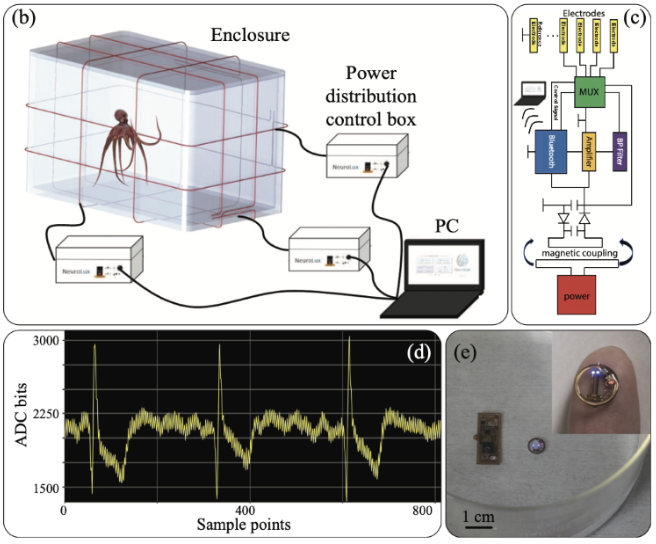

Cephalopods, including the cuttlefish, octopus, and squid, possess one of the most advanced nervous systems among invertebrates. With their advanced nervous systems, cephalopods are able to perform sophisticated behaviors such as navigating in open water to search for food. Yet how their nervous systems accomplish spatial navigation remains completely unknown. On the other hand, much work has been done in mammals, especially the rodent, to reveal the part of their nervous systems underlying spatial navigation. In particular, neurons in the hippocampus exhibit spatially-selective activity that is thought to provide an internal estimate of animals’ current location. This brings up an interesting question: do cephalopods, with their lineage diverges from the vertebrates more than 500 million years ago, evolve a similar or distinct strategy in their nervous systems to solve the navigation problem? To address this question, this project aims to record neuronal activity in the octopus brain while the octopus perform a spatial navigation task. This work has the potential to reveal essential neuronal mechanism underlying spatial navigation, irrespective of different animal species.

Instructor

Ernie Hwaun

Ernie completed his PhD in Neuroscience from the University of Texas at Austin. He is interested in how neurons connect with each other to support cognitive functions such as memory. To tackle this problem, Ernie has been using in vivo extracellular recording techniques to obtain neuronal activity while animals perform a memory task. Besides research, Ernie enjoys playing basketball with friends and reading manga.

Email:ernie214@stanford.edu